Why Mars Missions Must Go Through the Moon First

When Apollo 13's oxygen tank exploded 200,000 miles from Earth in 1970, the crew had exactly one option: swing around the Moon and limp home in four days. Now imagine that same catastrophe, but you're seven months from help instead of four days. That's Mars. There's no abort button, no emergency return, no rescue mission.

As space agencies and private companies race toward Mars missions in the mid-2030s, mission planners are making what may be the most important engineering choice in spaceflight history: the path to Mars goes through the Moon first. This isn't a detour or political compromise—it's a structural necessity driven by physics, biology, and the brutal mathematics of survival.

The Proximity Problem: Distance Determines Survival

The foundational principle reshaping Mars mission architecture is what experts call proximity-based risk management—the recognition that distance from Earth fundamentally determines which failures are survivable.

Want to go deeper? Listen to the 20-minute investigative deep dive on this topic.

Listen to EpisodeOn the International Space Station, orbiting 250 miles up, emergency evacuation takes hours. On the Moon, that same evacuation takes roughly three days. Mars changes the math completely. Depending on orbital alignment, a one-way trip takes six to nine months. Communication delays run between 4 and 24 minutes each way, eliminating real-time conversation with mission control.

"You're on your own in a way that no human being has ever been on their own before," according to space policy advocates including Christina Korp, who managed Buzz Aldrin's career and now leads the SPACE for a Better World foundation. Korp has emerged as a vocal proponent of what she calls an "environmental gradient" approach to Mars preparation—moving humans progressively further from Earth into harsher conditions while maintaining a safety net.

This reality has concrete design implications. Life support, medical capability, food production, psychological support, and equipment repair must all function autonomously for years. The question facing mission architects: how do you test systems that need to work perfectly in an environment you've never lived in, when failure means death?

The Moon as Humanity's Space Residency Program

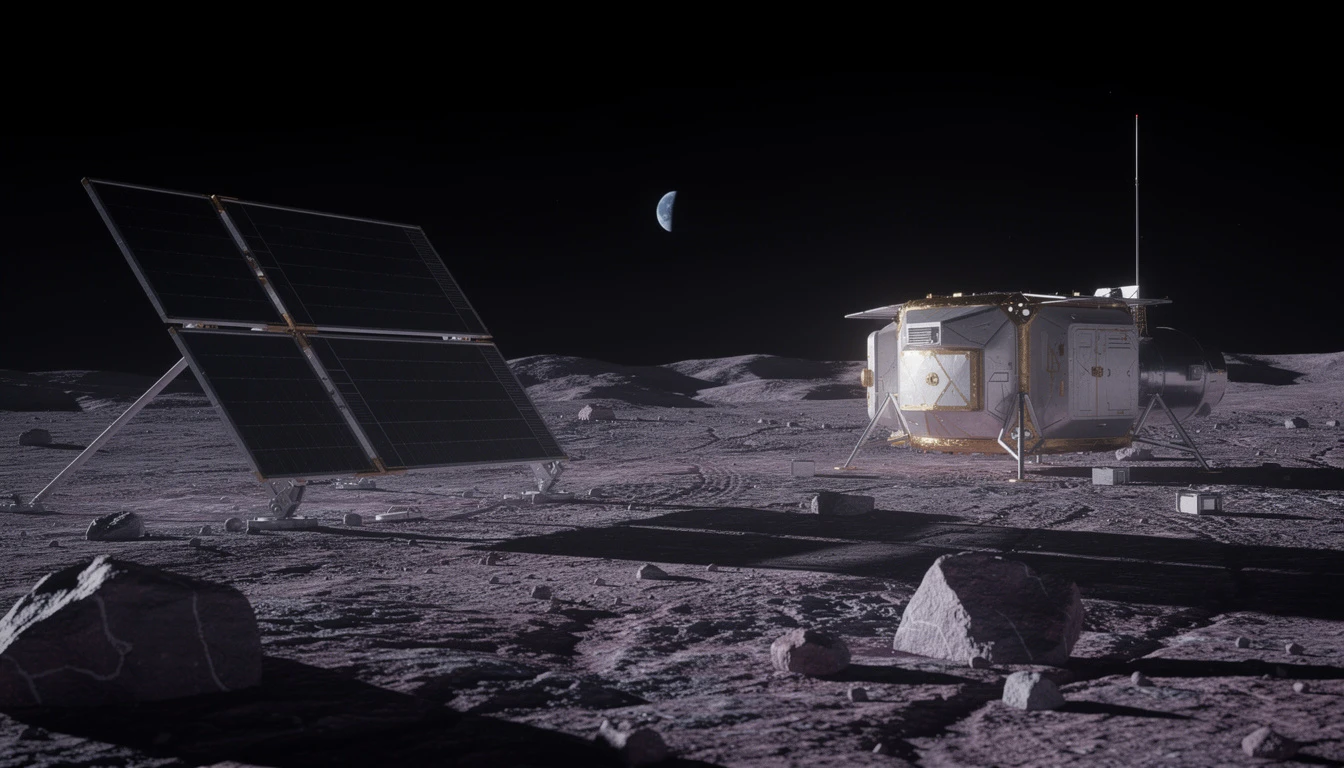

The answer emerging from NASA, the European Space Agency, and private space companies is that you test those systems on the Moon first. The lunar surface functions as humanity's residency program for deep space—a proving ground just three days from Earth where every system failure is survivable and every lesson transfers directly to a planet 140 million miles further away.

The Apollo missions provided a total of roughly 16 person-days on the lunar surface across all six landings—less time than a two-week vacation. NASA's Artemis program aims to extend that dramatically, with the goal of sustained presence: weeks, then months, then eventually permanent habitation. Each extension tests systems under real conditions that no Earth-based simulation can replicate.

While Earth-based analogs like Antarctic research stations and underwater habitats provide valuable data, they cannot reproduce one-sixth gravity, lunar regolith characteristics, the radiation environment, or the psychological reality of knowing the nearest hospital is a quarter-million miles away.

Three Critical Challenges the Moon Helps Solve

Regolith: The Insidious Dust Problem

Lunar dust proved one of the most operationally challenging aspects of Apollo missions. Gene Cernan called it the single biggest problem on the Moon. The particles are sharp, jagged, electrostatically charged, and cling to everything—abrading seals, clogging mechanisms, and irritating lungs.

Mars presents its own regolith challenges, with soil containing perchlorates—toxic chemical compounds hazardous to human health. But the mechanical challenges of dust management—keeping it out of habitats, protecting equipment, filtering air systems—transfer directly from lunar experience. Engineering a habitat seal that keeps out lunar dust for six months solves most of the dust ingress problem for Mars.

Radiation: Testing Shielding in Real Conditions

Outside Earth's magnetosphere, humans face exposure to galactic cosmic rays and solar particle events. The Moon's surface, with no magnetic field and essentially no atmosphere, exposes astronauts to roughly 60 times Earth's radiation levels. Mars is slightly better, with its thin atmosphere reducing surface radiation to about 40-50 times Earth levels. But the seven-month transit through open space is where cosmic ray exposure truly accumulates.

The Moon allows testing of radiation shielding materials, monitoring of long-term biological effects, and development of countermeasures—all within three days of Earth's medical facilities. Scientists can study how the human body responds to chronic radiation over months and iterate on shielding designs. On a Mars transit, there's no iteration.

Partial Gravity: The Unknown Variable

The International Space Station has generated extensive data on microgravity's effects: bone density loss of 1-2% per month, muscle atrophy, cardiovascular deconditioning, and vision changes. But there's almost zero data on partial gravity.

The Moon's one-sixth gravity and Mars's three-eighths gravity are neither zero gravity nor Earth gravity. They're something in between, and scientists genuinely don't know how the human body responds to years at those levels. Short lunar stays during Apollo weren't long enough to generate meaningful physiological data. Extended stays of weeks to months on the Moon would provide the first real experimental data on partial gravity adaptation.

This represents one of the most significant gaps in current knowledge. Mission planners are preparing to send humans to live on Mars for potentially years at a time, in a gravitational environment that has never been studied in any sustained way.

Beyond Survival: Resource Independence

The fourth dimension reshaping lunar strategy involves In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU)—learning to use what's already there rather than launching everything from Earth at costs of $10,000-$20,000 per kilogram to low Earth orbit, and far more to lunar or Martian surfaces.

The Moon becomes not just a training ground for human biology, but a testing facility for resource extraction, processing, and manufacturing technologies that will be essential for Mars self-sufficiency. Water ice at the lunar poles, oxygen extraction from regolith, and 3D printing with local materials all require validation before deployment on Mars.

What to Watch

The success of extended Artemis missions over the next decade will largely determine the timeline and feasibility of crewed Mars missions. Key milestones include establishing sustained lunar habitation beyond 30 days, demonstrating closed-loop life support systems, and generating the first longitudinal data on partial gravity's effects on human physiology.

The decades-old Moon-versus-Mars debate has been reframed not as a choice between competing destinations, but as recognition that one is prerequisite for the other. The Moon isn't a stepping stone in a poetic sense—it's a controlled experiment filling in blank pages of a textbook that must be written before attempting Mars.

As space agencies and private companies finalize architectures for 2030s Mars missions, the question is no longer whether to go to the Moon first, but whether mission planners fully understand why it's the only responsible path forward.