Moonshot: Our Cosmic Survival Strategy

Explore humanity's next giant leap as experts unravel the crucial role of lunar exploration in preparing for Mars missions. This episode reveals why the Moon isn't just a stepping stone, but a critical training ground for survival in space. Discover how physics, biology, and resource engineering make lunar missions essential for safely expanding human presence beyond Earth, challenging long-held assumptions about interplanetary travel.

Deep Dive

Synopsis

When Apollo 13's oxygen tank exploded 200,000 miles from Earth, the crew had exactly one option: swing around the Moon and limp home in four days. Now imagine that same catastrophe, but you're seven months from help instead of four days. That's Mars. There's no abort button, no emergency return, no rescue mission. You survive with what you have, or you don't.

As space agencies and private companies race toward Mars missions in the mid-2030s, mission planners are making a decision that might be the most important engineering choice in spaceflight history: the path to Mars goes through the Moon first. This isn't a detour or a political compromise—it's a structural necessity driven by physics, biology, and the brutal mathematics of survival.

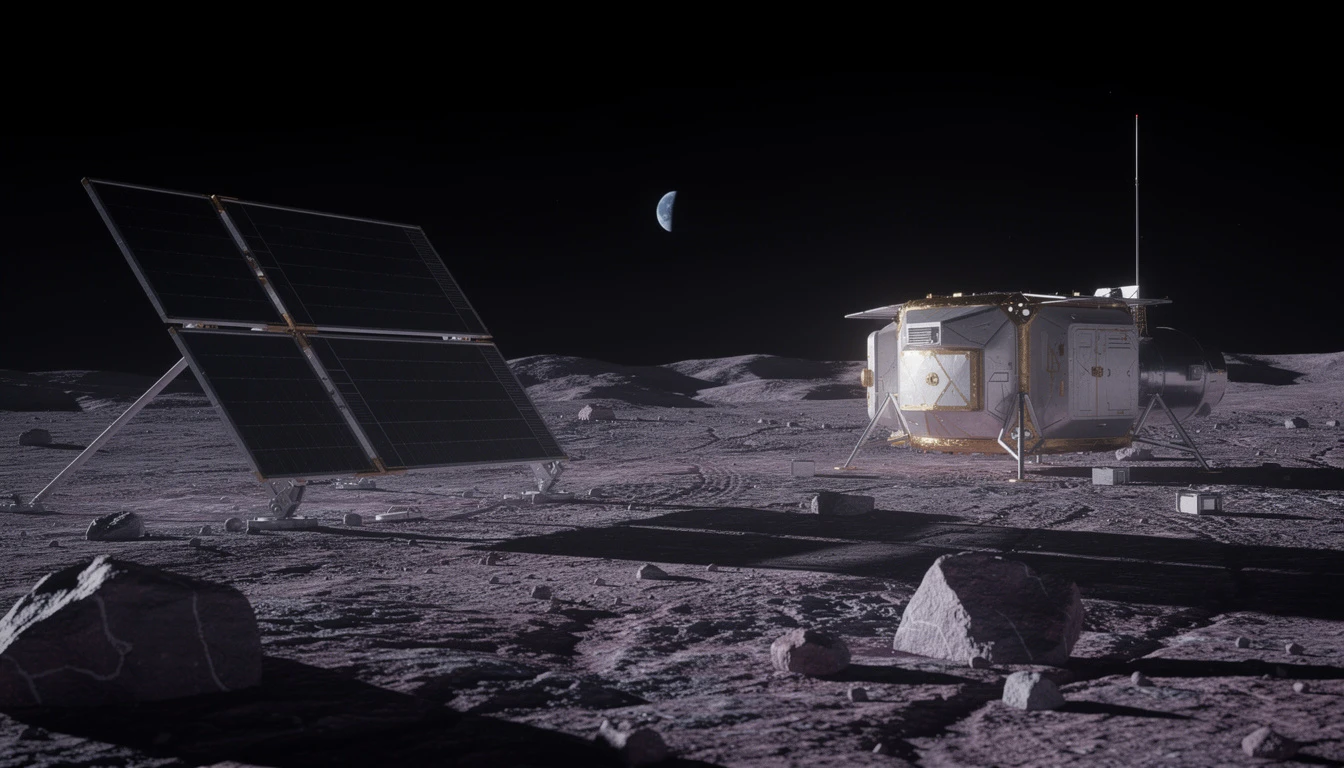

The Moon functions as humanity's residency program for deep space—a proving ground just three days from Earth where every system failure is survivable and every lesson transfers directly to a planet 140 million miles further away. From the insidious dangers of razor-sharp regolith that destroyed Apollo equipment, to radiation exposure 60 times Earth levels, to the still-mysterious effects of partial gravity on human physiology, the lunar surface presents challenges that no Earth-based simulation can replicate.

Experts including NASA mission architects and space policy advocates like Christina Korp reveal why proximity-based risk management fundamentally reshapes how we approach Mars. You can't test life support systems designed for years of autonomous operation by simply launching them toward Mars and hoping they work. The Moon offers the environmental gradient needed to build complexity gradually—establishing base camps on the way to the summit rather than jumping straight from sea level to Everest's peak.

This episode dismantles the decades-old Moon-versus-Mars debate by showing they were never competing destinations—one is the prerequisite for the other.

Key Takeaways

- The Moon is not just a detour to Mars, but a critical training ground that allows humans to progressively test and develop systems for long-duration space missions with a safety net of proximity to Earth.

- Mars missions present unprecedented survival challenges, including 6-9 month travel times, 4-24 minute communication delays, and complete mission autonomy, making rigorous pre-mission testing essential.

- Lunar environments provide unique testing conditions that Earth-based simulations cannot replicate, such as one-sixth gravity, specific regolith characteristics, radiation exposure, and extreme psychological isolation.

- The current space exploration strategy involves a deliberate "environmental gradient" approach, where lunar missions serve as a supervised training ground before the high-stakes, solo "practice" of Mars missions.

- Lunar regolith (moon dust) presents complex engineering challenges, such as abrasive particles that clog mechanisms and irritate lungs, which must be solved before attempting more distant planetary missions.

- Extended lunar missions are crucial for developing sustained human presence in space, moving beyond the brief 16 person-days of the Apollo era to weeks, months, and eventually permanent habitation.

- Emergency response and life support systems must be designed for complete autonomy, with every component capable of functioning perfectly for years without external resupply or intervention.

Read Full Transcript

Chapters

Click to jump to section